By Dan Taylor (Colombia II) The first excerpt takes place in Moniquirá, Boyacá. Luis Eduardo is a Promotor de Acción Comunal, Kent is a Colombia I Volunteer and Dan’s partner.

“Our task was to select a few veredas and get the juntas reorganized and functioning. Then they could determine some useful projects. That was the theory anyway.

Our first job doing this was more or less successful. Working with the Coffee Federation, we came up with the most likely vereda to achieve some success and organized a meeting. Kent, Luis Eduardo, and I, along with a home economics teacher and an agricultural extension agent, rode around the vereda talking up the meeting and handing out invitations. In the end we managed to get eighty people out one Saturday morning and proceeded to hold an election. It took place in a little run-down schoolhouse the community had built themselves many years ago. I had taped posters on the walls which explained with words and sketches the democratic process, the qualities needed for junta officers, and what acción comunal is all about. The campesinos politely filed in, hats in hand—women wore hats also—and looked at the posters.

“How many of you can read?” the home economist asked.

It turned out almost none. They were looking just because they felt it was expected of them. She then explained the posters and finally everyone was crowded into the room, sitting on the rickety benches or standing three deep along the walls.

Luis Eduardo explained the procedure and the election began. I don’t recall if there was any other business with home economics or agriculture. The extension agents were probably there just to be supportive. In the United States, we grow up with organizations, elections, and democracy in general. These people did not have that exposure, although community action is deeply rooted in Latin culture.

Somehow, we developed a list of nominees for the junta board who people could vote for. The tendency was for the biggest show of hands for the first candidate announced. Luis Eduardo would carefully explain, do it over, start with the last nominee first, and finally something like a fair election occurred, although the home economist and I were counting hands, and she had to continuously admonish people for voting two or three times. Finally, the election was over. The mayor, who also attended the meeting, swore in the officers, and speeches were made. I even sweated through a five-minute speech I had to write out beforehand and memorize word for word, my Spanish still pretty bad. Did that outward training help me here?

I doubt it, but maybe a little.

I wasn’t entirely satisfied with what happened. Training had given me an idealistic conception of community action based on the Puerto Rican model and those lectures from the anthropologist on the Pima reservation. This meant talking to people, maybe for years if necessary, until they realized the need for organization and came up with the idea on their own. We had done it in two weeks. I didn’t feel the people were ready—we hadn’t built trust with them yet.

However, this turned out to be our best election. We had several more, each seemingly worse than the last. I felt Luis Eduardo did too much leading, not giving people enough chance to express themselves. Kent and I also were feeling led around. We were developing a resentment which Kent expressed and I held back. We wanted to slow down and concentrate on a few veredas. The promotor was continually getting us involved, even reaching out into another municipio.

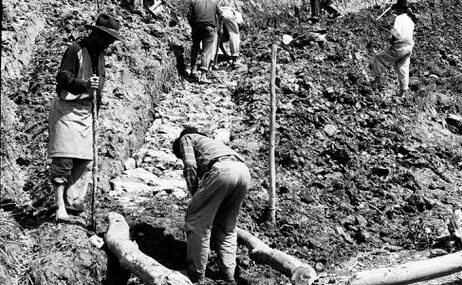

We did have one successful work party improving a trail. It was seven o’clock, the time we had agreed to start. The sky was clear and promised the usual sunny morning. Luis Eduardo and I had arrived at the spot where we were to begin improving the trail. We had picks, shovels, and sledgehammers which we had borrowed from the municipio. But where were the people of Tierra Castros? By seven thirty I was mad and ready to leave when one guy showed up. Barefoot with an old felt hat and patched, pin-striped trousers, he wanted to know where to begin. Soon another man came, and another, and then another, until there were thirty of us. We began to work.

The task was to widen the path and pave it with rock so that men on horseback and mules, and children carrying jugs of water could pass without sinking into the mud. By ten the potholes were filled in, the path widened, and side slopes neatly made. Drainage ditches had been constructed along each side, and a small bridge built to carry traffic across a larger ditch and onto the main road. We were ready for rock. Kent had been in town making sure the promised dump truck would arrive, which it did, more or less on time. We spent the afternoon paving the trail and had the job completed by the end of the day. My anger had turned to satisfaction and admiration toward the campesinos for their skills and their hard work.

I am ashamed of one aspect of this work in hindsight. The campesinos wanted to place large flat rocks as the paved surface. I felt horse’s hooves would slip on these rocks, which they some- times did, especially when shod. I wanted more of a gravel path. Not able to convince anyone, I attempted to crush the rocks as much as I could with the sledgehammer, pretending I couldn’t understand when someone tried to tell me differently.

Eventually I acquiesced and we did it their way. Despite sometimes slipping, I never witnessed an animal go down, and after all, roads had been built this way since Roman times. Who was I, the know-it-all gringo, to think I had a better way?”

Excerpt two is in Jardiń, Antioquia. Dan is serving as a volunteer leader in the area.

“A major blow for me occurred on October 4. That was the day my friend, Fred Detjen, died. I hadn’t really known Fred that long, and we didn’t actually see that much of each other in the last year and more, but I considered him a solid friend and his early death was a shock.

Losing him hit me hard, coupled with some subsequent events, all of which I will discuss in a later chapter. But throughout the month, I had to manage my grief. For the most part I kept it buried, hidden even from myself, but it would pop up from time to time.

Volunteers were seemingly pouring into Colombia, with some coming to Antioquia. By now volunteers from Group VIII had been settled in and more

were coming. Peace Corps administration was getting concerned about too many volunteers congregating and creating a negative image. That was certainly a concern of mine in Medellín.

But we made a decision to go just the opposite direction for one day in Jardín. I don’t know who had the original idea, maybe a combination of the mobile physical education unit and the sports director in Jardín, but I was fully supportive and helped organize it. We had seventeen Peace Corps volunteers in town for a sports field day. It began in the afternoon with us playing a volleyball game in the girls colegio. Aside from nearly knocking the Virgin Mary off her pedestal, it went great. There was a large crowd there to watch the funny gringos. Probably for the first time, they were seeing volleyball with teamwork and long volleys, but they also watched us make mistakes and take pratfalls, which made more of a show.

Then in the evening there was a big event in the boys colegio that cost sixty centavos to attend. It included a gymnastic display by the colegio boys, the singing of anthems—the Antioquian anthem, the Colombian, and ours. The evening was capped with a basketball game. One side had the four physical education volunteers from Medellín plus Chuck, with Darryl and Phil refereeing, and the rest of us on the other team. By the second half, the differ- ence really began to show. So while it wasn’t the greatest game, Kevin, one of the physical education volunteers from Medellín, put on a great display of long shot swishes and hook shots. At the half he held a small hook shot clinic, which went over well. All in all it was a fun day, and we had nothing but positive feedback. It also went a long way in picking up my spirits after Fred’s death.”