Recruitment Stories

From College to Peace Corps

By Darrel Young

Site Location: San Pablo, Nariño

I was strolling across campus, about to begin my last semester of undergrad, looking toward law school in the fall. Venturing into the Student Union, I saw folks gathered round the presidential inauguration in progress, and sat down to watch. And then, Kennedy began to speak.

His speech, his intelligent speech, not just his elegant words but even more so the compelling cadence of his voice, zapped right into my emotional wiring, stirring parts of me I never knew existed. A transcendent charmer he was, challenging us to share ourselves with the world in ways reflecting our shared humanity. I just had to ask not.

Kennedy did not mention Peace Corps in his inaugural, but it soon entered my expanded consciousness. I sent in an application, and in early June, got a telegram from Sargent Shriver to report to Rutgers University for training to go to Colombia. I immediately looked up Colombia on the map, RSVPed in the affirmative, and that has made all the difference in my life.

I will always honor the memory of JFK. If not for him, I never would have given myself over to strange people in a strange land, soon feeling strangely at home. I never would have discovered, having no Latin blood in me, those parts of myself that are, indeed, Latin. I never would have realized what texture there is to life, what moments there are for our own making.

I never would have known my self…beyond myself.

Inspired by Kennedy

By Harold “Buck” Northrup

Site Location: Yolombo, Antoquia and Magangue, Bolivar

I was a junior in college. This dynamic, charismatic guy running for the presidency comes along talking about new initiatives, and introduces the idea of a peace corps. He was elected, I was fired up. He established the beginnings of the Peace Corps by Executive Decree to form the first groups, while a more permanent Peace Corps legislation bill wound through congress.

I applied as soon as applications opened. Was accepted for Colombia I, to work with communities in developing and realizing their potential, through the “Community Development” approach. What a great experience and personal sense of satisfaction. Totally changed my life and work life. After Peace Corps I worked with CARE, around the world, for 30 years. Then I worked with the International Rescue Committee for 6 years in the former Yugoslavia area (Bosnia, Herzegovina, etc.), southern and eastern Russia, northern Mid-East and western Asia.

What an impact Peace Corps had on me. I only hope that in turn, in some modest manner, I helped contribute to the improvement in the lives of others.

The Peace Corps Experience

By Barney Hopewell

Site Location: Medellin, Antioquia

Graduation was coming up in a couple of months and I had no idea what I was going to do next. I had taken the Peace Corps test and when the telegram came accepting me for a position in Colombia, I was beyond relieved and eager to get on with it. Having met Ted Kennedy at a university political rally early I was impressed with the “Kennedy” style and of course had heard the call to serve my country.

The alternative was volunteering for the draft or signing up for the Air Force that I had seen fairly close up in ROTC but this looked like a better choice. Having spent part of my childhood living in Mexico and on the southern border in Arizona, my Spanish was adequate and I hoped that by living in Colombia, I could achieve fluency. Near the end of training, I was selected as one of four Volunteer Leaders for our group of 62. Later on, I also helped with volunteer groups that came to Antioquia for health and sports programs. Even though my volunteer experience was not that of the typical volunteer in my group, that experience did lead me to a number of interesting jobs and to finding a wife, una mexicana, with whom I have shared a life of wonderful adventures for the past 55 years.

It also has enriched my life by having a continuing relationship with the Numero Unos that went off to Colombia in 1961 and still communicate regularly with each other con mucho cariño. One of our daughters joined the Peace Corps and served in Costa Rica where she had gone to third grade when I was there as an associate Peace Corps director for education. We have hopes that one of our grandchildren might take the same path one day.

My “Why Peace Corps?”

By Martin Acevedo

Site Location: Ebejico, Antioquia

I am Colombian born. I was in my final semester of Vocational Education at New York State University when I became aware of the Peace Corps recruiting efforts and needs. I was an Army Veteran and an idealist believing that Peace Corps was an opportunity for the USA to be one-on-one with the Colombian campesino and aid them to empower themselves across and beyond the stratified Colombian social and governmental structure. Peace Corps volunteers have achieved that goal by simply, leading by example, getting their hands dirty serving Colombian communities. Beyond Colombia, I have continued to serve my community in Ashland, MA.

Pre-Service Training Stories

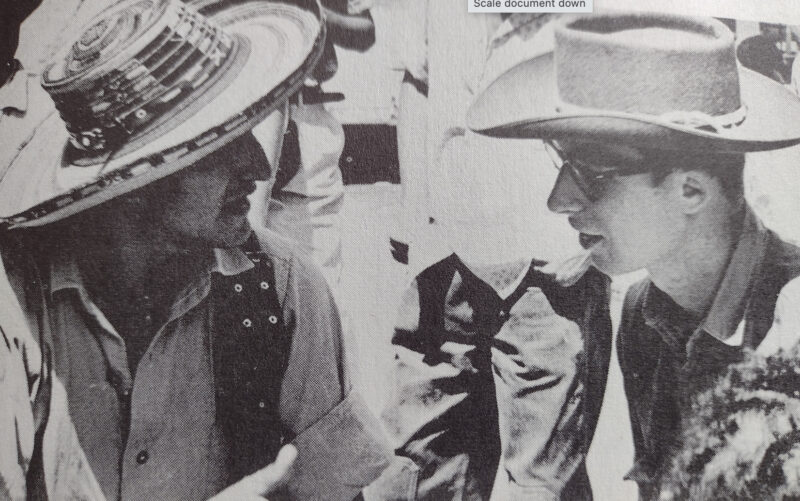

Shriver Meets Colombia One

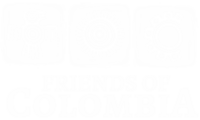

Sargent Shriver welcoming the Colombia volunteers at Rutgers University

By Ronald A. Schwarz

Site Location: Santa Cruz, Santander and Silvia, Cauca

On June 26, 1961, Sargent Shriver arrived at Rutgers University to meet Colombia One, the first group of volunteers for his new Peace Corps program. He was ill at ease, with reason. The plan for Colombia One called for 120 to 140 trainees but the selection committee complained about “the paucity of good, fully qualified candidates” and their final list included just 84 names. A TIME magazine reporter described the scene: “Looking more like the freshman football team than America’s latest weapon in the cold war, the first contingent of Peace Corps volunteers sat in creaky wooden bleachers in the middle of the Rutgers University campus…”

For more than two months news about Latin America dealt with Cuba and the Bay of Pigs disaster and Shriver acknowledged that we were in troubled times, “This may be our last chance to show that we are really qualified to lead the free world . . . “ Sarge ended his remarks and opened the meeting to questions. As the Q & A session was ending, Shriver revealed that an unidentified clothing manufacturer had offered to outfit the entire corps with blue jeans but that he had to refuse the donation. A volunteer in the second row asked, “Why did the Corps reject the offer?” Shriver replied, “We had to turn him down because it’s against the law.”

I was seated in the front row, and, to make sure the media heard the question, shouted at Sarge “Then, why don’t you change the law?” Shriver stared at me for a long moment, surveyed the group and smiled. Ten weeks later, waiting in Idlewild International Airport to board a four-propeller, Avianca Super Constellation to Bogotá, we were handed duffle bags filled with clothes, boots and flashlights, courtesy of Sears and Roebuck. For many of us, more important than the bag’s contents was a not-so-hidden message from Shriver: “I’ll take care of Congress, you guys just get your butts to Colombia and get the job done.”

Stories from Peace Corps Service

The Greatest Challenge

By Tom Mullins

Site Location: Fuquene, Cundinamarca

At the end of a 4 mile dirt road 80 miles North of Bogota, Fuquene was a small municipality of about 2,000 small rural farms that rested on top of the cordillera at 9,000 feet. Our team of three lived in a small room in back of the church. We took our meals in a tienda on one side of the plaza. A bus came up the mountain once a week at 4:30 AM to transport farmers and goods to a nearby town market.

The needs of the community were common: school, health center, road extending to the next village. We made trips to Bogota with the leaders of the previously organized junta de accion communal to secure services like a bulldozer, cement and an ingeniero. We made frequent visits to the campo to encourage families to participate when possible in the mingas for projects we hoped would enhance the community.

On one such visit, we approached a single dwelling, introduced ourselves and were invited inside. As we sat in the dirt floor living room, I noticed two pictures on a wall: the Pope and John Kennedy. The family of five children spaced between 12 and 4 years old, offered us scotch in simple small flowered glasses. Even at 10 in the morning, it was not unusual to be treated to the best they had. Faustino took the lead in covering the basics about accion comunal and what our role was in the community. After 45 minutes, we were invited to their dining room table where a big bowl of ajiaco stew, rich with one less chicken in their yard, potatoes and corn. This was not their usual weekday lunch but they honored us with the best they could provide. To me it said a lot about these humble people who probably had never entertained guests from outside their municipio.

After mass the following Sunday, we greeted the same family who had turned out to help make bricks for the future health center. The priest who lived in a nearby village came to Fuquene for mass and funerals. But he always “encouraged” parishioners to participate in the minga following mass. This village that long-suffered political violence in it’s Colombian past, wanted nothing for free but agreed to do their share of labor if the government also contributed.

Thinking back on my experience in Colombia, while it changed everything for me as it led to working in Latin America, using my Spanish, marrying a volunteer who served in Bolivia and influenced our family plans by adopting two children from El Salvador, I am somewhat embarrassed to have assumed a gringo, 20 years old, never outside of the country with poor Spanish could land in a small rural mountain village in the Andes and be a force for change. While the village was glad to have us there and some improvements were made, I think the greatest change was in myself.

The First Peace Corps Fatalities

By Ronald A. Schwarz

Site Location: Santa Cruz, Santander and Silvia, Cauca

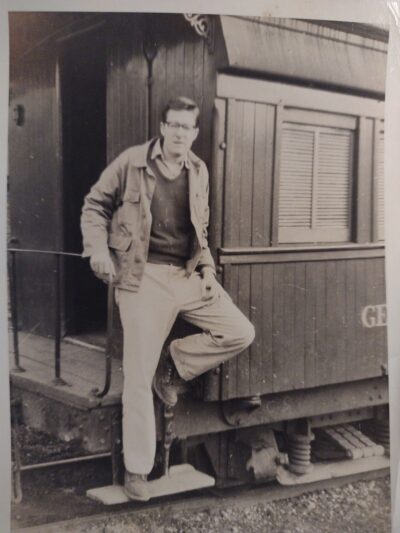

In late April 1962, tragedy struck Colombia One; a handful of volunteers hustle airplane seats after spending their Easter vacation in the Chocó – a vast jungle region bordering the Pacific coast. The first plane out, an AVISPA DC-3, is overbooked and has room for only two volunteers. David Crozier and Larry Radley get on board. A few hours after takeoff the plane is reported missing and a search is quickly organized. The Colombian government and the U.S. Army send planes and helicopters but find no trace of the aircraft. A few days later the wreckage is spotted near the top of a steep mountain ridge. The tropical vegetation is dense; it is impossible to land the chopper, and a descent by cable is too risky. An attempt to reach the site on foot also fails.

On April 29th, a week after the plane was reported lost, a team of five men led by a Colombian Air Force officer and a U.S. Army Captain make a hazardous descent by cable from a helicopter hovering over the crash site. They build a landing pad and are joined by three Colombia One Volunteers, Ned Chalker, Steve Honoré and Barney Hopewell. Ned’s report of the scene reads, “the people were unrecognizable, there were no whole bodies. Heads and arms and other pieces much too terrible to describe were lying around.” The Peace Corps has its first fatalities.

Colombia One PCVs Ned Chalker, Steve Honoré and Barney Hopewell confirm the identity of the dead Volunteers by their Sears boots. An official ceremony is held and the ground is sanctioned as a cemetery. Before departing, the rescue team constructs several wooden crosses. The remains of all passengers and crew are still at rest on the mountainside. On June 6, 1962 Colombia’s Ministry of Education issues a decree honoring the memory of “ . . . dos servidores de Colombia:” David Crozier and Larry Radley

Following the death of their son, the Croziers’ hand Sargent Shriver a copy of a letter they received from David. The last line reads: “Should it come to it, I would rather give my life trying to help someone than to have to give my life looking down the barrel of a gun at them.” Shriver hangs a framed copy of the letter on his office wall. The Peace Corps acknowledges David and Larry’s sacrifice by naming two training sites in Puerto Rico after them: Camp Crozier and Camp Radley.

Why JFK Owes Me

By Bill Woudenberg

Site Location: Miraflores, Guaviare and Cali, Valle del Cauca

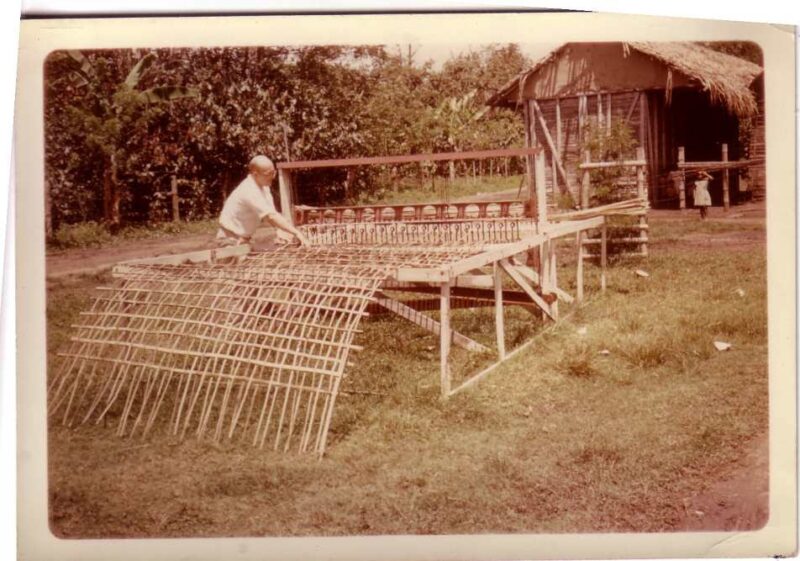

Initially I went to Miraflores but didn’t like it. I transferred, went south and when I got there I found a vine-like plant which was like bamboo. And I thought, ‘why don’t we weave that together and make nets out of it, for fencing or latrines.’ All the work of building one was done in no time. So I drew a sketch and wrote to Mert Cregger ‘This is what I want to do, but I don’t want to do it here, I want to do it in Cali.’ He agreed and I started building this loom, which could weave these strips of bamboo with wire, to make a fence, or to make the revetment panel to cover the latrine hole. It prevented the sand from caving in.

In 1962 the Peace Corps was desperate for things to show off. JFK was asking, ‘What’s Peace Corps doing around the world?’ Pictures of my loom went right to the White House so JFK could see it. And at the World’s Fair in Seattle, there was a big picture of me and the loom along with a write-up about the project; together they covered an entire wall.

Stories About Returning Home

By Ned Chalker

Site location: Titiribi, Antioquia

After making all the arrangements to have my Peace Corps trunk shipped home from Medellin, I bought a ticket for the island of San Andres to visit some old friends before returning home. I loved San Andres and had visited a few times during my two year service in Colombia. One evening on the island I was asked to speak to some of the locals about what I did in Titiribi. The subject was Community Development. Not expecting many people to show up I took my time getting to the meeting place. When I arrived there were about 700 people waiting to hear my stories. We ended the evening singing the Colombian national anthem, followed by the US national anthem…in English …they all knew it! Everyone seemed to speak some form of English on San Andres. It was a powerful moment to remember.

The following day, I got on an old C-40 cargo plane and for $10.00, flew from San Andres to Miami. What a deal! Upon landing my first impression of the States was that everyone wore glasses and shoes. It was truly culture shock. While it was great to be back, I was already missing Colombia, which had become a part of me.

The Day We Became Kennedy’s Orphans

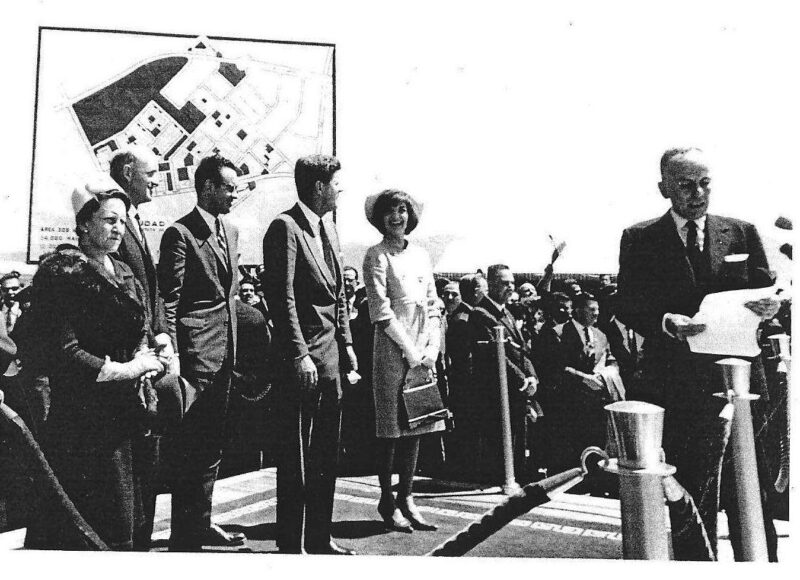

President John K. Kennedy and First Lady Jackie Kennedy in Colombia, December 1961

By Ronald A. Schwarz

Site Locations: Santa Cruz, Santander and Silvia, Cauca

The noontime news on my car radio reported that the President was in Dallas, Texas. Any mention of JFK boosted my adrenaline and brought back memories. In September 1961 members of Colombia I met with JFK in the East Room of the White House. And, several months later, the President and Jackie were welcomed by millions of Colombians and two-dozen volunteers in Bogotá. The love affair between Latin Americans and our Catholic President was pervasive and mystical. His picture was posted on mud walls of huts throughout the country. Volunteers in Colombia and the rest of Latin America were referred to in the media as los hijos de Kennedy – Kennedy’s children. The connection opened hearts, doors and countless bottles of beer.

In 1963 in the USA, the Peace Corps was expanding; up to 100,000 a year was a number kicked around. Members of Colombia One completed overseas service on June 24, 1963. About half the group were hired by the Peace Corps to work at Washington headquarters, as staff in Latin America and in training programs all over the country.

I was in the anthropology program at Michigan State University and in the late morning of November 22, 1963. While at the supermarket, shopping cart in hand I moved up and down the isles paralyzed by the choices displayed on the shelves. I was maneuvering around two middle-aged ladies when the store loudspeakers emitted a high-pitched screech followed by a somber announcement: President Kennedy had been shot and taken to a Dallas hospital. I was stunned but hopeful.

I listened as one of the ladies whispered to her companion, “Perhaps this will be good for the country.” Her words left me speechless, in shock. I left my cart, exited the supermarket and returned to the house I shared with two other grad students. I turned on the TV and watched Walter Cronkite tell us that President Kennedy was dead. Like tens of millions of Americans and Colombians, my soul was punctured and filled with grief; Kennedy’s Children were now his Orphans.