By: Abby Wasserman

December 2008

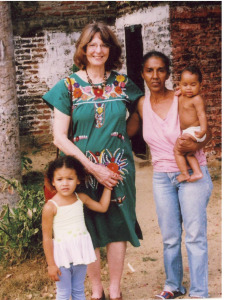

My little Ana is a grandmother. There’s white in her wiry black hair and she is missing teeth. It wrings my heart to see her so fragile. Ana was my compañerita for a year in Dibulla, La Guajira, in 1964 and 1965, when I was a PCV there. Ana’s younger sister, my goddaughter Clea, is tall and robust. Mentally, she is still a child. She lives under the watchful eye of her mother, Ida.

As Armando turns the taxi around to leave, Lilibet and Carlos tell me that the people of Rio Ancho were vulnerable when the violence began in La Guajira because their village lay right on the path from the Sierra Nevada. Their relationships were loosely woven, so paramilitaries and drug lords could divide and conquer. There were killings and kidnappings and stolen land. I would like to ask someone if José, Clara and Berto survived, and what happened to El Martillo and his family. But the ghost of recent violence, and the knowledge that we will have only a few hours in Dibulla, hasten us along. We have been told to return to Santa Marta by nightfall. So we bump back on to the highway. There’s a sense of unease in Rio Ancho, as though violent men have only moments before passed through and will soon return.

May 2009

As we approach the Dibulla turnoff, Lilibet tells me that when paramilitaries tried to establish a base in town, they were rebuffed. “We don’t want you here” apparently is all it took to bar their entry. It seems fantastic. If Dibulla could bar paramilitaries, avoid the kidnappings and murders that have plagued La Guajira, why couldn’t other communities do the same? It’s a vexing question and there’s no way I’ll find the answer in a three-hour visit. Nine years ago when my site partner Howard returned to La Guajira, his driver refused to turn into Dibulla. Now we rapidly cover the six kilometers on a paved road. The landscape is altered: hectares of plantain trees have been cut down and burned. Carlos says the landowner will cultivate rice, diverting water from the Dibulla River to flood his fields. Water levels in Sierran rivers, including the Dibulla, are low due to siphoning off by cocaine producers in the mountains. The rivers are weakened by the time they empty into the ocean, so the strong saline tides push their way further inland.

I want to say that Cárdenas was a good man who cared about Dibulla and that his death was a tragedy, that her uncle was a sinverguenza (without shame), that my friend Chave’s heart was broken, that I sat with her beside the body part of one night in a house cleared of furniture. I say none of this. Why burden her with old griefs? We visit Olimpia Coronado de Moreu, who with her husband Wilson owned a bus, general store, and the movie theater (now boarded up) where I used to watch U.S. westerns. They were first citizens of Dibulla but kept aloof from community development efforts. She’s in her eighties now, her face softer and more friendly than I remember. Wilson has died. Her daughter invites us in for coffee, but we decline. A cup of tinto would require slowing down to Dibulla time, a luxury we don’t have. I’m sweating profusely. My Mexican cotton dress sticks to my back. It doesn’t catch the breeze like the long, bat-wing Guajiran manta. In mestizo society the Wayuu Indians were considered inferiors. I had a few mantas made, and when I wore them I stood with the Wayuu in a small way that gave me satisfaction but probably compromised my status in Dibulla.

Ana is thin with finely etched wrinkles. Her voice is low and husky and she’s missing teeth. Yet she still looks like the little girl Ana. “I cried so when you left,” she says. “Why didn’t you take me with you?” This is a surprise; was the subject even broached back then? Would I have taken her if asked? No. I married Bill Rayman, had children, moved around the world. Peace Corps was a two-year detour in the life I was meant to live. Or so I thought.  The baby is Ana’s granddaughter, one of two she cares for while her daughter attends school in Santa Marta. The highway has made an enormous difference but not, perhaps, for Ana. I ask, “How has your life been?” Ana lowers her head. “He sufrido” (“I have suffered”), she says.

The baby is Ana’s granddaughter, one of two she cares for while her daughter attends school in Santa Marta. The highway has made an enormous difference but not, perhaps, for Ana. I ask, “How has your life been?” Ana lowers her head. “He sufrido” (“I have suffered”), she says.

December 2009

When I first entered Ida Campo’s mud and palm frond hut in 1964, her daughter Ana was 10 years old—dark, slim, and quick to laugh. Now she’s 51 and stands gravely with a grandbaby on her hip. I sense that life has pressed her hard. I would like to be alone with her to talk, to listen, but we’re surrounded by friendly people welcoming me back to Dibulla after 42 years. Carlos, the cameraman, is taking video footage. His sister, Lilibeth, is interviewing me for television. My goddaughter, Clea, stands close. Ida’s relatives and friends converge. One hour in Dibulla and I’m drowning in sensation and memory.

Ana tells me, “Voy a traer fotos de mi familia,” and after I assure her I will wait to see her photographs, she departs. But before she can return, Lili says it’s time for lunch, and we leave Ida’s. We walk a few blocks— where the street has been opened up for sewer pipe repair—and are welcomed by Rafa and Yuye, Lili and Carlos’s parents, heads of a big and accomplished family. We’re served cold drinks, and as lunch isn’t quite ready and as the cemetery is nearly next door, I excuse myself for a brief visit to what was once my shortcut to the beach. The graves are poorly maintained and crowded with stacked crypts and plastic flowers. I once photographed old Juana Bueno sitting on a crypt, legs crossed, eyes closed, chin resting on one hand. Juana liked the cemetery, too.

Dibulla Cemetery

Carlos announces that the town mayor has returned after meeting with President Uribe in Santa Marta. A childhood friend of Carlos and Lili’s, el alcalde is young, educated, and ambitious for his home town. We’re invited to his office, where he listens but says little, seeming to take my measure. Finally, I ask him if there is anything I can do for Dibulla. He has the answer ready. “Tell people Dibulla is safe and a good place to come for a vacation.” I wonder how much infrastructure there is even now for tourism, but I know I would go to Dibulla for a vacation—string up a hammock and stay, watching the sea by day and the stars by night. I say I will spread the word.

I will learn later from Alba Lucía Varela how Fundehumac in Santa Marta works with families to set goals and ways to achieve them, and how interested parties like myself can provide money through Fundehumac to support the effort. The key is a personal commitment—theirs. When I hear this I am filled with joy. To work with a family as a whole, taking everyone’s needs and goals into account—this is something I can embrace. I always thought that I was a poor Peace Corps Volunteer. I built no roads or schools or latrines, formed no lasting organizations, bettered no one’s life. I spent a lot of time listening and learning, not much doing.

I will learn later from Alba Lucía Varela how Fundehumac in Santa Marta works with families to set goals and ways to achieve them, and how interested parties like myself can provide money through Fundehumac to support the effort. The key is a personal commitment—theirs. When I hear this I am filled with joy. To work with a family as a whole, taking everyone’s needs and goals into account—this is something I can embrace. I always thought that I was a poor Peace Corps Volunteer. I built no roads or schools or latrines, formed no lasting organizations, bettered no one’s life. I spent a lot of time listening and learning, not much doing.